Echo has fascinated humans for centuries. Whether heard in vast canyons or designed intentionally in a recording studio, its ability to repeat and transform sound has shaped music, architecture, and technology. In nature, echo is a simple reflection of sound bouncing off surfaces, yet in audio production, it becomes a powerful creative tool. From the earliest myths to modern digital delay units, the manipulation of echo has evolved dramatically.

Early recording engineers experimented with echo chambers, capturing natural reflections to enhance depth and space. The rise of tape echo in the mid-20th century introduced the iconic slapback sound in rock ‘n’ roll, while digital delay revolutionized how echoes could be controlled and shaped. Today, echo remains an essential element in music production, used to add dimension, movement, and emotion. This guide explores its origins, technical evolution, and its lasting impact on sound recording.

What is Echo: Historical Approach

Echo is a delayed repetition of sound caused by reflection. When a sound wave bounces off a surface and returns to your ears, it arrives late enough to be heard as a separate event. This phenomenon has fascinated people for centuries. It also shapes the way we design rooms, create music, and capture audio. Over time, engineers and musicians have found ways to control, imitate, and enhance echo. These methods led to creative breakthroughs in recording technology. Echo now plays a vital role in both acoustic science and modern studio production.

Origins of Echo in Nature

Natural echo occurs wherever there are solid, reflective surfaces. Large canyons, caves, and vast halls produce audible repeats when you shout or clap. The distance to the reflecting wall determines how long it takes for the sound to return. Sound travels at about 343 meters per second, so a far wall can yield a noticeable delay. If the delay is long enough, your brain registers it as a distinct echo.

People used to believe echoes carried mystical or magical meanings. Ancient storytellers described them in myths or legends. Over time, scientists started investigating echo as a physical event. This led to a deeper understanding of how sound waves behave. Eventually, we learned how materials, angles, and distances affect reflections. That knowledge became crucial for architectural acoustics. Designers began to incorporate specific features to enhance or reduce echoes in auditoriums.

Some famous natural settings highlight dramatic echoes. For example, certain mountain ranges and rocky valleys can throw a voice back multiple times. In these locations, you might hear a repeating “hello…hello…hello…” that slowly fades. Each repeat arrives weaker and sometimes more muffled than the last. Observers noticed that higher frequencies tend to lose energy faster, creating darker-sounding echoes over long distances. These natural observations laid groundwork for later studio innovations.

Echo Chambers and Early Recording

Engineers sought ways to artificially recreate echo in early recording studios. They built echo chambers, which were dedicated rooms with reflective surfaces. By playing a recorded sound through a speaker inside the chamber and capturing it again with a microphone, they obtained realistic echoes. These chambers became prized studio assets. Different chamber sizes yielded various echo lengths. Harder surfaces offered brighter reflections, while more absorbent materials provided darker, shorter echoes.

Studios famous for their echo chambers included well-known facilities that influenced the sound of popular music. Sometimes, a small tile room delivered crisp, lively echoes. Other times, a larger, curved chamber produced longer and more dramatic tails. Engineers experimented by changing microphone placements or speaker positions inside these rooms. By adjusting distance to the walls, they shaped the timing and strength of the returning echoes.

Musicians embraced chamber echoes because they added warmth and space to recordings. In the days before digital effects, this technique was one of the few methods for giving vocals or instruments a sense of depth. Producers recognized that adding a gentle echo could make a performance feel more immersive. If they wanted a stronger effect, they could turn up the output from the chamber microphone or move it closer to a reflecting wall. This process required time, experimentation, and an ear for balancing direct and reflected sound. As a result, early recordings with chamber echo achieved a unique resonance that still captivates listeners.

Tape Echo and Slapback

Tape echo revolutionized how people created delayed repeats. Engineers attached extra playback heads to reel-to-reel tape machines, allowing a signal to be recorded and played back a short time later. That fixed amount of travel time gave the first practical adjustable delay effect. Early adopters discovered that this repeated signal, known as slapback, thickened vocals and guitars.

Slapback usually consisted of a single repeat with a short delay time—often around 100 milliseconds. This was enough to create the illusion of a lively space without drowning the original signal. Rockabilly and early rock ‘n’ roll recordings heavily relied on slapback to shape a signature sound. Musicians, like Elvis Presley, used tape echo to give their voices a distinct vibe.

Tape machines introduced some natural filtering to each repeat. Over multiple passes, the echo lost brightness and gained slight saturation. These imperfections became part of its charm. Producers learned that adjusting tape speed changed the echo time, while feedback controls allowed multiple repeats. Eventually, specialized tape echo units, such as portable boxes, emerged. They let guitarists, singers, and mixers fine-tune echoes on stage or in small studios. Despite their mechanical limitations, tape echo machines remained popular. Their warm tone and pleasing decay still influence the design of modern digital delay plugins.

Digital Delay Revolution

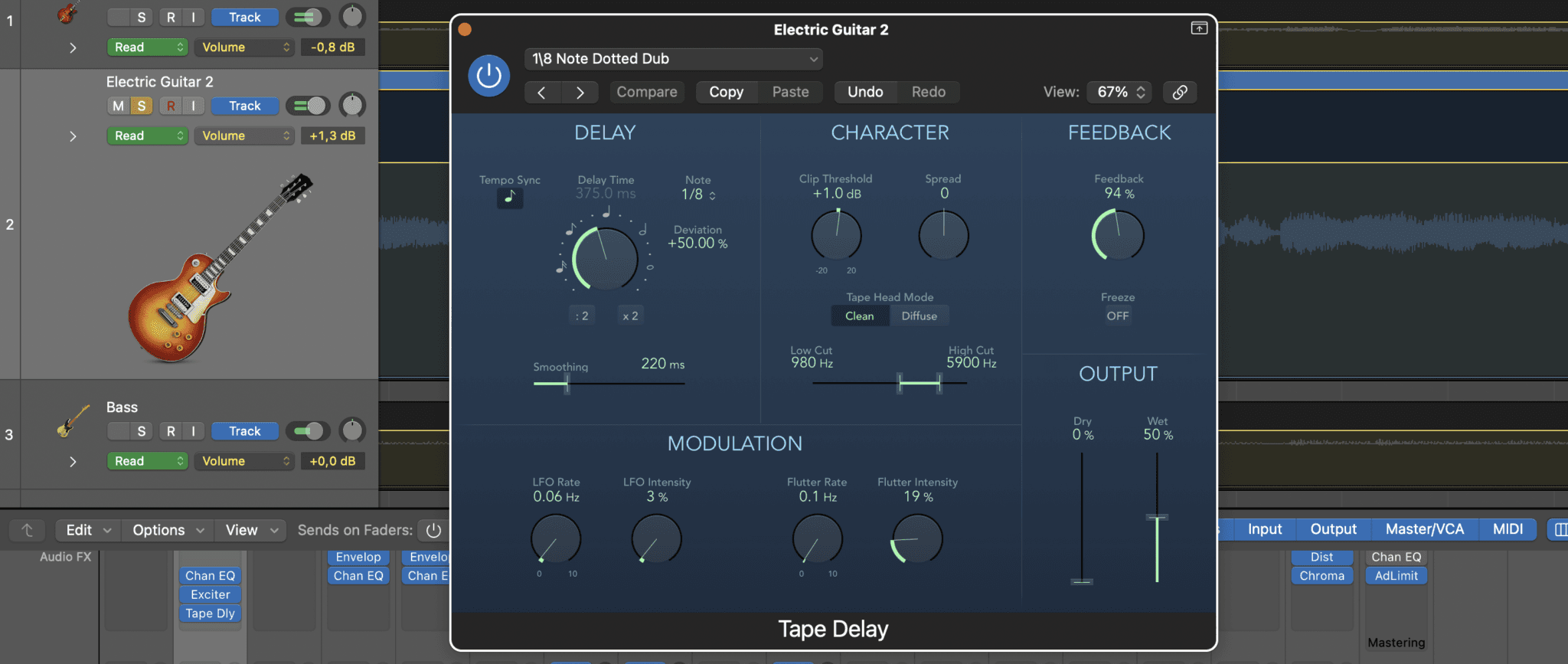

Digital technology arrived with the promise of precise, noise-free echoes. Engineers developed digital delay units that sampled incoming audio and replayed it after a programmable interval. Unlike tape, digital systems delivered consistent quality. They also gave instant control over delay times, repeat patterns, and feedback. Musicians could tap tempos, switch delay subdivisions, and store presets.

Digital delay effects became a staple in guitar pedals, rack units, and later in software plugins. They covered a range from short doubling echoes to long, sweeping repeats that spiraled into self-oscillation. Feedback filtering was added to mimic the natural dampening of real echoes. Advanced units offered stereo ping-pong modes, where the sound bounced between left and right channels. This innovation opened creative possibilities for producers. One guitar performance could morph into a rhythmic tapestry of cascading repeats.

Today, digital echo is everywhere. Home studio enthusiasts use stock delay plugins, while professionals reach for advanced software with detailed modulation controls. Some digital delays even emulate classic tape characteristics, reproducing the warmth and pitch instability of vintage gear. The versatility of modern echoes goes beyond music. Film sound designers add them to convey vast spaces or dramatic tension. Game developers integrate them to simulate the size of virtual worlds. After decades of evolution, echo remains central to our experience of recorded sound.

How Is Echo Used in Music Production?

Echo shapes space, rhythm, and emotion in countless music genres. A single echo can create a bouncy slapback, or multiple echoes can paint lush landscapes of cascading repeats. Producers use echo to thicken individual parts, highlight transitions, and impart a signature sonic color. By varying delay times, feedback, and filtering, they can evoke anything from a retro rockabilly vibe to a futuristic electronic swirl.

Vocal Echo Techniques

Singers frequently rely on echo to enhance presence and add an otherworldly feel. A short, single echo can give vocals extra punch without cluttering the mix. Known as slapback, this effect works well for driving rock or blues. Longer echoes generate more dramatic results. Delays timed to a song’s tempo often fill gaps between phrases, creating call-and-response patterns. Many pop ballads feature a trailing echo on the last word of a line, letting it linger for impact.

Engineers often place a filter on the echoes. They remove high frequencies so repeated words sound softer or more distant. This keeps the direct vocal clear and upfront. Sometimes, a moderate reverb is also added to the delayed signal. It blends the echoes into a wider ambiance. Another advanced approach is ducking delay, where the echo’s volume lowers while the singer is actively performing, then rises in pauses. This strategy prevents the echo from overwhelming the main vocal line. By fine-tuning these techniques, producers keep echoes both present and tasteful, supporting the emotion in the song.

Guitar Echo Methods

Electric guitars benefit immensely from echo. Even a subtle delay can add a sense of roominess to lead lines or solos. Many guitarists experiment with pedalboard delay units. These range from simple analog stomps that replicate tape echo warmth to complex digital processors offering pristine repeats. Players time their phrases to interact with echoes, creating rhythmic interplay.

Some guitarists use ping-pong delay, bouncing notes from left to right in the stereo field. This approach delivers a wide sound that occupies more space in the mix. Others use dual delays with different timings. A short delay might thicken each note, while a longer delay provides a second echo trail. Stacking these layers can turn a single guitar into a vibrant, multi-dimensional instrument. In certain genres, like shoegaze or psychedelic rock, high feedback settings create swirling waves of repeats that become part of the overall texture. Echo also pairs well with distortion or modulation effects. It can extend sustain and produce dreamy soundscapes that invite the listener to get lost in the ambience.

Creating Rhythmic Patterns

Echo can become a rhythmic tool. Producers set delays to subdivisions of the song’s tempo, such as quarter notes, eighth notes, or dotted eighths. Each repeat lands in sync with the beat. This approach transforms simple riffs into a driving pulse. U2’s The Edge popularized this style, using tempo-synced echo to form percussive patterns. Each guitar note dances with its own echoes, filling space between strums. The effect can be mesmerizing, especially when combined with a steady drum groove.

Drummers and electronic producers also harness synchronized echoes on hi-hats, snares, or synth stabs. The repeated hits create interlocking rhythms. In some electronic dance music, echoes form an integral part of the groove. Producers automate feedback levels so echoes gradually build and then fade, creating tension and release. This dynamic interplay can be more effective than static loops. Rhythmic echo can shape entire sections of a track, adding momentum or surprise. By carefully controlling volume, panning, and filter sweeps, producers craft evolving echoes that enrich arrangements.

Subtle Echo for Depth

Not all echoes are dramatic or obvious. Subtle delay settings can create depth without drawing attention to themselves. Engineers use short delays—sometimes under 50 milliseconds—to thicken a sound. These micro-delays do not register as distinct repeats. Instead, they make a track feel fuller. For vocals, gentle stereo delays can widen the image, simulating multiple voices. On acoustic instruments, a slight echo can mimic the reflections of a real room. The result is a natural sense of space that doesn’t sound overly processed.

Mixers often keep these low-level echoes tucked beneath the main signal. They add dimension without distracting the listener. A small bump in feedback might extend the decay just enough to feel supportive. In busy arrangements, subtle echo ensures elements remain cohesive. It prevents everything from sounding flat or too dry. This approach is popular in modern pop, R&B, or even orchestral recordings. Sometimes, a more noticeable echo would compete with important melodic lines. By leaning on delicate delays instead, producers preserve clarity while maintaining a rich ambience.

Differences Between Echo, Reverb, and Delay

Echo, reverb, and delay can be confusing terms. They all involve reflections of sound, yet they each serve different purposes. Knowing how they differ helps you choose the right tool for shaping space, rhythm, or ambiance. This section clarifies each concept, then shows how they overlap in practical scenarios.

Understanding Echo

Echo is a distinct repeat of a sound, heard clearly as a separate event. You say something, then a moment later you hear it again. Real echo needs a noticeable gap—often longer than 50 milliseconds—to be perceived as a second signal. In nature, echoes occur when sounds bounce off distant walls or cliffs. In audio production, echo is generated with delay units. Longer delay times create more noticeable echoes. Shorter delay times produce a tighter feel. Feedback settings can stack echoes repeatedly, decreasing in volume each cycle. The simplest echo might be a single bounce, called slapback, which is perfect for retro rockabilly. Multiple echoes can also evolve into rhythmic patterns or swirling atmospheres.

What Is Reverb?

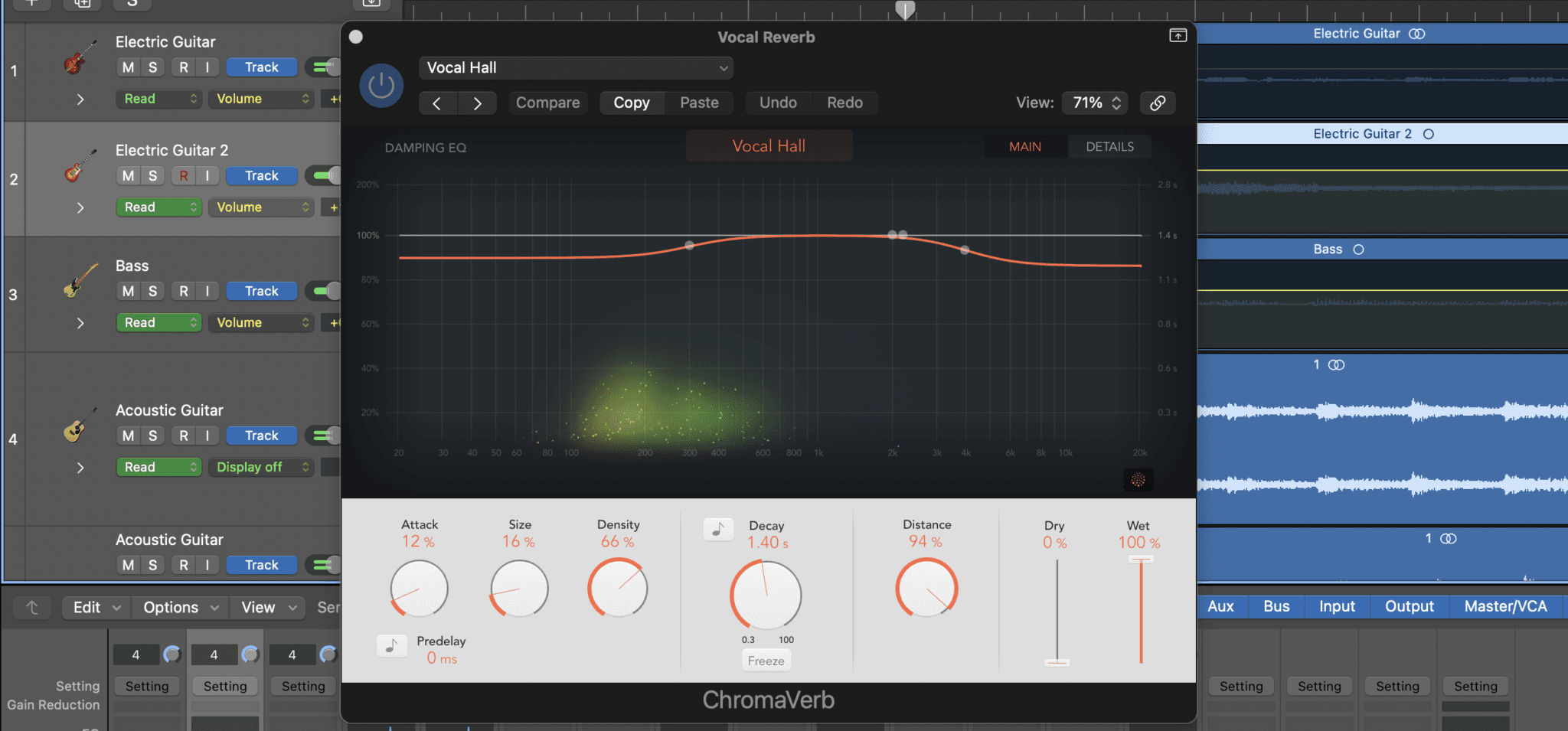

Reverb is a dense wash of reflections. So many reflections arrive in quick succession that the brain perceives them as a continuous decay. Imagine clapping in a church or a large hall. You don’t hear distinct echoes. Instead, you hear a smooth tail that fades slowly. The size and materials of the space affect how long the reverb lasts and how the sound disperses. In audio production, reverb plugins or hardware simulate these overlapping reflections. Engineers might choose a hall reverb for a spacious, grand effect, or a room reverb for a tighter, more intimate space. Because reverb is made of countless mini echoes, it adds ambiance without discrete repeats. This is ideal for blending instruments together, giving a performance a natural or sometimes ethereal background.

Exploring Delay

Delay in music technology is the effect or device that holds an audio signal for a set time, then releases it. By adjusting this time, you can create anything from subtle doubling to extended echoes. Many devices call this effect delay even if it produces obvious echoes. Some pedals or plugins label themselves as echo units, though they do the same basic function. Modern digital delays offer extensive control over feedback, tone filtering, and stereo placement. Analog or tape delays exhibit more character. They often roll off high frequencies and introduce slight saturation, creating a warm and vintage-sounding repeat. Whether you call it delay or echo, the core process remains: record the input, store it briefly, and play it back later.

Key Practical Distinctions

Echo is commonly understood as a separate, repeated sound. Reverb is a blur of many small reflections. Delay is the mechanism that produces these repeats. In production, you might use a delay unit to achieve the effect of echo. You might also chain multiple delays to form a reverb-like wash, although that’s less common. If you need a direct repeat for a rhythmic pattern, you reach for a delay set to specific intervals. If you want to place a performance in a realistic acoustic space, you add reverb. These distinctions guide creative decisions. Yet in practice, producers sometimes combine them. For example, they might add reverb to the echo return, creating a spacious trailing effect. Or they might feed a reverb into a delay for experimental washes of sound. Understanding the core differences lets you mix them effectively.

Examples of Echo Used in Famous Songs

Throughout modern music history, echo has played a pivotal role. From early rockabilly to contemporary pop anthems, producers and musicians leveraged echo to define their signature styles. This section highlights several standout tracks. Each one uses echo in a way that influenced future generations of artists.

Elvis Presley and Slapback

Elvis Presley’s early recordings popularized slapback echo on vocals and guitars. This effect arrived via tape delay setups. Engineers positioned extra tape heads so the sound repeated quickly, typically under 120 milliseconds. The result was a single, sharp repeat that made the voice or guitar twang with liveliness. This slapback gave rockabilly records an upbeat energy. It also reinforced Elvis’s unique vocal presence. Fans sometimes called it the “Sun Studio sound,” referring to the legendary studio known for pioneering tape echo methods. The technique spread to other rock ‘n’ roll icons. It became a hallmark of 1950s and 1960s recordings, forever linked to the birth of modern pop-rock styles.

U2’s Rhythmic Delay

U2’s guitarist, known as The Edge, built a signature sound around tempo-synced delay. He meticulously timed echoes to fit the beat, often using dotted eighth notes. When he played a chord or riff, the echo bounced back in rhythmic alignment. This approach turned simple guitar parts into elaborate interwoven patterns. One prime example is “Where the Streets Have No Name.” The cascading echoes fill in space between his picked notes. They add momentum and depth, making the band’s sound expansive. This technique transformed a raw guitar line into a driving force. Many guitarists studied The Edge’s delay approach. They copied his methods to create their own layered textures.

Dub Reggae Echo

Dub reggae producers in the 1970s and beyond relied on echo as a main effect. They fed drum hits, vocal snippets, or horn lines into feedback-heavy delays. The echoes repeated multiple times, sometimes spiraling off into deep, murky tails. Tape echo units, such as modified reel-to-reel machines, became iconic in Jamaican studios. Those producers also used reverb and filtering, making the echoes darker and more resonant with each bounce. The swirling repeats became a trademark of dub mixing. Tracks felt spacious, hypnotic, and continuously evolving. This focus on echo influenced other genres, including hip-hop, electronic dance music, and experimental rock. Many modern mixers still employ dub-like echo techniques to create trippy, immersive atmospheres.

Modern Rock and Ambient Echo

Contemporary rock, post-rock, and ambient artists embrace long echo tails and layered feedback. Bands use digital delay pedals to loop haunting riffs. Repeats overlap in lush textures, filling sonic space without standard chord progressions. In ambient or shoegaze music, guitarists crank feedback on a delay pedal. The sound swells into a flowing wash, where individual notes melt together. Some artists combine multiple delays, each with unique timing or filtering, to build complex sonic landscapes.

Vocals can also receive huge echoes to convey otherworldly depth. These modern echo techniques owe their origins to earlier pioneers. However, advanced digital technology now pushes them further. Producers can manipulate delay times on the fly, sync them to electronic rhythms, or morph them into reverb-like swirls. The result is a broad sonic palette for emotive and cinematic sound design.

Conclusion

Echo remains a timeless and transformative force in audio. From early studio chambers to state-of-the-art digital plugins, its evolution has shaped how we record, mix, and experience music. A simple delayed repeat can define an entire genre or highlight a single moment in a song. By adjusting echo settings, producers guide listeners through vast spaces, tight rooms, or swirling rhythmic tapestries. Understanding echo’s natural roots, the differences between reverb and delay, and the variety of uses in music production is essential.

Armed with this knowledge, you can craft echoes that bring songs to life or let them gently float in the background. Echo is both science and art. It’s the fascination of hearing your voice bounce back from a distant canyon, and the creativity of reproducing that magic in a recording. By combining tradition with innovation, audio professionals continue to push echo into thrilling new frontiers.

About the Author

Néstor Rausell

Singer, Musician and Content Marketing SpecialistNéstor Rausell is the Lead Singer of the Rock band "Néstor Rausell y Los Impostores". Working at MasteringBOX as a Marketing Specialist

Leave a comment

Log in to comment